HOW TO Align the Hidden Curriculum of RM Education?

Maribel Blasco (Copenhagen Business School)

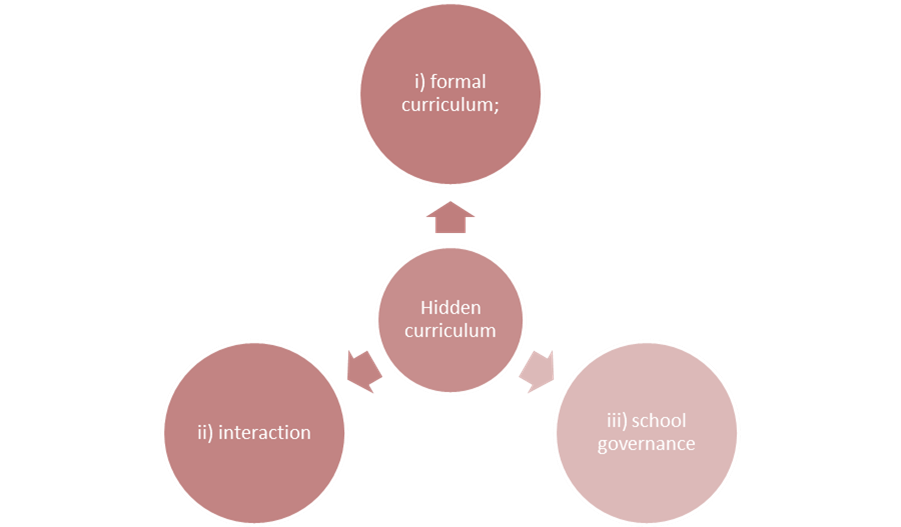

Abstract: Graduates are reputedly still leaving business school with poor morals, despite considerable focus on responsible management education? The ‘hidden curriculum’ (HC) directs the attention to the idea that what is taught in educational institutions is not necessarily what is actually learned. The HC operates through many areas of business schools, most notably in i) formal curriculum; ii) interaction; and iii) school governance. This means recognizing that changing curricula alone is not enough to bring about transformation in students’ moral attitudes because signals about appropriate conduct are communicated in so many subtle ways beyond formal curricular content. We should ask ourselves: “What are students really learning while I think I am teaching X?

Context: Why are business schools still reproducing poor morals among graduates?

How come graduates are reputedly still leaving business school with poor morals, despite considerable focus on responsible management education (RME)? Are we missing something?

It is not the first time that educators face this type of problem. In the 1970s and 80s, pioneering scholars like Pierre Bourdieu, Henry Giroux, Michael Apple, Basil Bernstein, Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis grappled to understand why, in an supposedly emancipatory and meritocratic age schools seemed to be reproducing the very status quo – e.g. in class, gender, and race – that the education system was supposed to iron out. Many of these researchers were inspired by reproduction theory and the concept of hegemony, and they found a powerful analytical tool to study this question in schools and other educational institutions in the concept of the ‘hidden curriculum’ (HC), first coined by Philip Jackson in 1968.

Concept: The Hidden Curriculum as a wake-up call for management education

Like all powerful concepts, the idea behind the HC is as simple as it compelling. It may be defined as ‘“what is implicit and embedded in educational experiences in contrast with the formal statements about curricula and the surface features of educational interaction” (Sambell & McDowell, 1998, pp. 391-392). Giroux (1979) defines the HC rather more darkly as: ‘that covert pattern of socialization which prepares students to function in the existing workplace and in other social political spheres’. At any rate, the basic point is that what is taught in educational institutions is not necessarily what is actually learned, and that the knowledge and meanings communicated are inseparable from the world outside the classroom where they reflect ‘the interests of the most powerful groups’ – in other words they are never value neutral (Edwards & Usher 2003: 5; Mayo 1999: 36).

This insight opens up the possibility that there may be inconsistencies between what the school declares to be its values compared with the real messages it communicates about “what really matters” and what constitutes appropriate conduct (Sambell & McDowell, 1998, p. 392). Might this help to explain why business students seek to pick up the wrong messages about ethics even though teachers deliver all the ‘right’ content? The covert socialization that occurs through the HC transmits tacit values and norms about what constitutes correct behavior which have been found to strongly influence students’ own values and ethics learning and behavior (Trevino & McCabe, 1994). It manifests through many of the things that teachers tend to take for granted as ‘just the way the system works’, including a school’s structuring of time, rules of conduct, assessment procedures, traditions, induction courses, incentives and sanctions (Gair & Mullins, 2001; Sambell & McDowell, 1998; Wren, 1999). ‘The familiar world’, writes Bourdieu (1989: 18), ‘tends to be “taken for granted,” perceived as natural’ and hence dismissed as trivial or even irrelevant. From a HC perspective, then, what might constitute this familiar, taken for granted world in management education?

Here are a few examples from three key areas of management education where the HC operates: the i) formal curriculum; ii) interaction; and iii) school governance.

First, the organization of the formal curriculum (and not just the content) carries meaning. For instance, if CSR is only offered in electives or is hived off into a single lecture at the end of a mandatory course, this sends a powerful signal to the students about the topic’s prestige and priority. Course content is another important area, but no only in terms of the choice of theories, models and examples taught but also the way they are taught, i.e. critically or uncritically. For instance, teachers always have the option to choose whether they present a model such as Porter’s Five Forces as the model for conceptualizing competition within an industry, or whether to present competing models and encourage students to discuss the implicit assumptions of these, e.g. that in Porter “companies must compete not only with their competitors but also with their suppliers, customers, employees and regulators” (Ghoshal, 2005, p. 75).

Content delivery is another key HC area: the stories, images, examples, metaphors, and representations (see Stepanovich, 2009) deployed in teaching represent success and failure, role models and antiheroes in ways that are far from value-neutral. Images of business people on Powerpoint slides need not always depict older white males in suits, for instance. Neither are the didactic strategies through which content is delivered, e.g. ‘signature pedagogies’ such as cases studies, value-free (Ehrensal, 2001; Schmidt-Wilk, 2010). Second, interactions among school actors are important socialization moments and a major component of the HC (Apple, 1971; Lave & Wenger, 1991), which may support or undermine PRME goals. Such interactions occur both during formal teaching and outside of it and may be passed on from one generation of school actors to the next. They include anecdotes, folklore, traditions, jokes, stories, and stereotypes (Elkin, 1995; Hafferty & Franks, 1994).

Finally, governance is a major but often taken for granted area where HC messages are transmitted that may conflict with the school’s explicit values. One example of contradictory messages at my own school is the sponsoring of lecture theatres by powerful but CSR-challenged companies. Every year, students note the irony of attending lectures on CSR in a room sponsored by a tobacco multinational. Schools should lead by example by aligning responsibility goals with school practices, for instance, in relation to sustainability (e.g., implementing initiatives to cut CO2 missions, save on printing, etc.), or combating misconduct such as plagiarism or fraud. They may also act as role models by supporting diversity, for example, by working to support equal gender, generational and ethnic representation among faculty, and in their marketing materials (brochures, websites, etc.). Leading by example also applies to the people or companies that schools hire and endorse.

Application: Is what we think we teach really what students learn?

As a teacher, the insight that teaching is a package in which content perhaps plays only a minor role in what students actually learn, changes everything. Using the hidden curriculum concept begs the question: ‘what might students actually be learning while I think I’m teaching them about X?” It also means recognizing that changing curricula alone is not enough to bring about transformation in students’ moral attitudes because signals about appropriate conduct are communicated in so many subtle ways beyond formal curricular content.

Theories are a reflection of their time. The HC concept has fallen out of fashion in mainstream educational research in today’s age of hyperliberalism and bright-siding, when the notion that agents may be bound by social structures is abhorrent to many. Precisely because of this, awareness of the hidden curriculum is more urgently needed than ever.

More…

For deeper reading

References

Giroux, H. A., & Penna, A. N. (1979). Social education in the classroom: The dynamics of the hidden curriculum. Theory & Research in Social Education, 7(1), 21-42.

Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms. Teachers College Press.

Mayo, P. (1999). Gramsci, Freire and adult education: Possibilities for transformative action. Palgrave Macmillan.

McLuhan, Marshall. (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill.